Now, the new DBS device in his brain uses wires to helps deliver constant stimulation to keep his focal epilepsy manageable and has reduced his seizure frequency to just a few every month.

Rylan is among less than a dozen pediatric patients and currently one of the youngest at Mott to undergo the procedure, which has more commonly been used in adults.

On New Year's Eve of 2018, then 7-year-old Rylan was playing with his cousins at his grandfather's house when he suddenly zoned out for a couple of minutes and stopped responding to those around him, the Molls quickly decided that something didn't feel right and took Rylan straight to the emergency room.

Neurodiagnostic tests showed no signs of a seizure, unusual brain activity or anything suggestive of epilepsy. Within a few hours, Rylan experienced yet another seizure-like episode.

"He was having what I would think of as a seizure," Alicea Moll said. "His mouth was clenched up, his eyes were fluttering back, he was stiff, and he couldn't move."

Rylan was quickly rushed back to the emergency room where he proceeded to experience multiple seizures that night. Eventually, the emergency room staff suggested that the family be taken by ambulance to University of Michigan Health C.S. Mott Children's Hospital.

At Mott, Rylan was hooked up to an electroencephalogram (EEG) machine. Pediatric epileptologists Sucheta M. Joshi, M.B.B.S. and Kerri L. Neville, M.D. confirmed that seizure activity was taking place in Rylan's brain.

"His scans have been challenging to find a clear-cut abnormality."

Erin Fedak Romanowski, D.O., Co-director, Mott Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery Program

Rylan started experiencing as many as four seizures a day. The cause of his epilepsy is unknown and not traceable to anything genetic or to a specific trigger. While this type of epilepsy is common for epileptologists to see, Rylan's case was particularly challenging since they couldn't locate where the seizures were coming from.

For a couple of years, Rylan's team of neurologists tried multiple different medications to try to keep his epilepsy under control. The medications would typically work for about a month and then lose all effectiveness. The starting location and trigger for the seizures was always changing.

"Some of his seizures would knock him out completely and he could not finish the day," Alicea Moll recalled. "We would take him out of school when he had a seizure, and he was missing a lot of instruction."

Rylan started experiencing as many as four seizures a day. The cause of his epilepsy is unknown and not traceable to anything genetic or to a specific trigger.

As Rylan's epilepsy appeared to be resistant to medications, it was time to consider surgery. The most common type of epilepsy surgery is to remove the part of the brain that is causing the seizures.

The second, palliative option is to consider neuromodulation, which includes responsive neuro stimulation (RNS) and deep brain stimulation (DBS). Both epilepsy surgery and RNS require a precise starting location in the brain for the seizures. Since Rylan's seizures could not be pinpointed to one specific spot, both options were ultimately off the table. This brought Rylan's team to their best option: deep brain stimulation surgery.

Despite the procedure being newer for the pediatric population, Rylan's history made him the perfect candidate. His family agreed that this procedure was the right choice and scheduled it for March 2022.

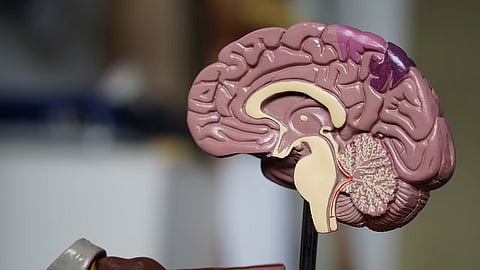

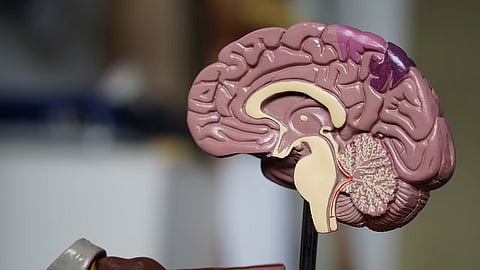

The goal of the DBS device is to continuously give stimulation on a cycle to the thalamus and reduce seizure activity.

This target in the thalamus is about the size of a grain of rice and is located in the center of the brain

"The area of the brain that we chose to stimulate is the anterior nucleus of the thalamus," said Rylan's neurosurgeon, Emily Lehmann Levin, M.D., who is the co-director of the U-M Health Department of Neurosurgery's multi-disciplinary Deep Brain Stimulation Program, one of the only centers that routinely treats children. "This target in the thalamus is about the size of a grain of rice and is located in the center of the brain."

"Hitting the thalamus accurately is important because if you don't get the electrode into the right spot it won't work," she said. Levin placed the device just beneath his rib cage so it is protected, and he can still play sports.

His seizures have been reduced to about two every four to six weeks thanks to the DBS device. When he feels a seizure starting, he presses a button on a remote that has been nicknamed the "bar of soap." The "bar of soap" communicates with the implant in Rylan (nicknamed the "Ironman Reactor") and creates a bridge for the device to communicate with a phone using Bluetooth.

Rylan will need to have another procedure in about two to seven years to replace the battery of the device. As he grows taller, the device will also be moved up to his chest. (PB/Newswise)