Approximately one-third of individuals diagnosed with heart disease experience sleep-related issues. A research paper featured in the journal Science, authored by a team from the Technical University of Munich (TUM), sheds light on the impact of heart diseases on the production of the sleep hormone melatonin within the pineal gland. This connection between the heart and sleep regulation involves a ganglion situated in the neck region. The study reveals a previously unknown function of ganglia and raises the possibility of potential treatments.

It has been previously recognized that melatonin levels can decline in patients with heart muscle ailments, such as after a heart attack. This phenomenon has been considered an illustration of how heart conditions can have systemic effects on the entire body. However, the team led by Professor Stefan Engelhardt, specializing in Pharmacology and Toxicology at TUM, and spearheaded by Dr. Karin Ziegler, the first author, has now demonstrated a direct causal relationship between sleep disturbances and individuals afflicted with heart conditions.

Ganglia as “electrical switchboxes”

"In our research, we unveil an intriguing connection between heart muscle issues and an organ that may initially appear unrelated," explains Stefan Engelhardt. The organ in question is the pineal gland, situated within the brain, which is responsible for producing melatonin. Similar to the heart, the pineal gland is governed by the autonomic nervous system, controlling various involuntary bodily processes. The nerves relevant to both organs emanate from ganglia, among other locations, with a particular emphasis on the superior cervical ganglion.

To grasp the essence of our findings, envision the ganglion as an electrical switchbox. In patients experiencing sleep disruptions following heart disease, it is akin to a problem arising in one wire within the switchbox, leading to a fire that subsequently spreads to another wire," illustrates Stefan Engelhardt.

Nerve connection to pineal gland destroyed in mice and humans

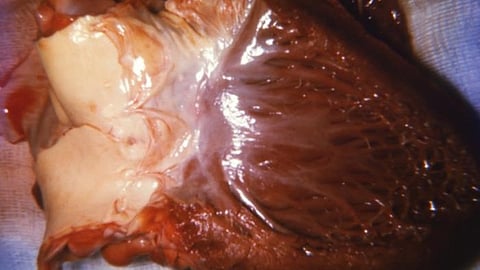

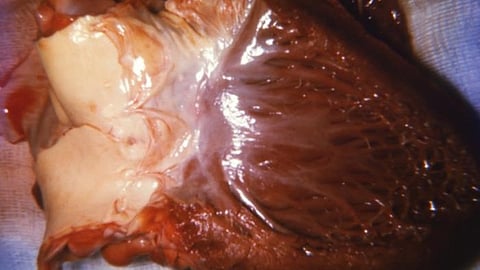

The team made a significant discovery involving the accumulation of macrophages, cells responsible for consuming dead cells, within the cervical ganglion of mice suffering from heart disease. The precise mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain a mystery. However, it was observed that these macrophages trigger inflammation and scarring in the ganglion, leading to the destruction of nerve cells. In both mice and humans, long fibers called axons extend from these nerve cells and connect to the pineal gland.

In advanced stages of the disease, a considerable reduction in the number of axons connecting the pineal gland to the nervous system was observed in mice, resulting in reduced melatonin levels and disrupted day/night rhythm in these animals.

Remarkably, similar effects were observed in humans. The team examined pineal glands from nine heart patients and found significantly fewer axons compared to the control group. Similar to the mice, the cervical ganglion in humans with heart disease exhibited scarring and noticeable enlargement.

Starting point for new drugs

The researchers hypothesize that the detrimental effects of dead axons become irreversible in the later stages of the condition. "In the initial stages, we managed to restore melatonin production in mice to its original levels by using medications to eliminate the macrophages present in the superior cervical ganglion," explains Karin Ziegler. "This not only highlights the significance of the ganglion in this process but also instills optimism that we can potentially develop drugs to prevent irreversible sleep disruptions in individuals with heart disease." Addressing this issue is one of the primary objectives the team aims to pursue in the forthcoming years.

Investigating ganglia for other possible connections

The study not only brings renewed hope for finding treatments for sleep disturbances in a considerable number of heart patients but also provides a fresh perspective on ganglia, according to Stefan Engelhardt. He highlights that advancements in techniques like spatial single-cell sequencing enable a much closer examination of individual nerve cells. This study may serve as a catalyst for researchers to systematically explore connections between different diseases in organs connected via ganglia, which function as crucial switchboxes. This could open up new avenues in the search for novel drugs.

Engelhardt further suggests that ganglia could also play a vital role in diagnostics. Notably, in the heart patients examined, all cervical ganglia were significantly enlarged, leading the researchers to speculate that this could serve as an indicator of heart failure. The ganglion's size can be easily assessed using a conventional ultrasound device. If subsequent studies validate these findings, it might be prudent to conduct more comprehensive heart examinations when an enlarged ganglion is detected. (HK/NW)