By Melba Newsome

During a routine visit to the Good Samaritan Clinic in Morganton, North Carolina, in 2018, Herbert Buff casually mentioned that he sometimes had trouble breathing.

He was 55 years old and a decades-long smoker. So the doctor recommended that Buff schedule time on a 35-foot-long bus operated by the Levine Cancer Institute that would roll through town later that week offering free lung-cancer screenings.

Buff found the “lung bus” concept odd, but he’s glad he hopped on.

“I learned that you can have lung cancer and not even know it,” said Buff, who was diagnosed at stage 1 by doctors in the rolling clinic. “The early screening might have saved my life. It might’ve given me quite a few more years.”

The lung bus is a big draw in this rural area of western North Carolina because some people aren’t comfortable going — and in many cases have no access — to a hospital or doctor’s office, said Darcy Doege, coordinator for the screening program.

“Our team makes people feel welcome,” she said. “We can see up to 30 patients a day who get referred by their primary care doctor or their pulmonologist, but we also accommodate walk-ups.”

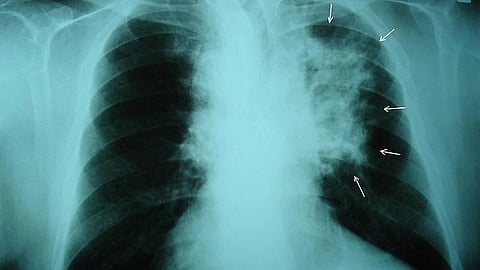

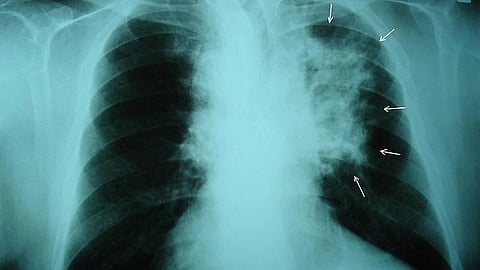

Lung cancer is the deadliest of all cancers. It grows quietly and is usually not detected until it has spread to other parts of the body. Early detection is key to survival, especially for someone at high risk like Buff, who is African American and has a history of smoking.

Although it is well documented that Black smokers develop lung cancer at younger ages than white smokers even when they smoke fewer cigarettes, the guidelines that doctors use to recommend patients for screening have been slow to reflect the disparity. If Buff had the same conversation with his doctor one year earlier, he would not have qualified for the CT scan that detected a nickel-sized growth on his left lung.

But screening is only part of the issue, said experts who evaluate what happens both before and after a person is checked for signs of cancer.

Researchers are concerned about the lack of diverse representation in the clinical studies on which the screening recommendations are based. For example, about 13% of the U.S population is Black, but Black people made up just 4.4% of participants in the National Lung Screening Trial, a large, multiyear study in the early 2000s that looked at whether screening with low-dose CT scans could reduce mortality from lung cancer.

Basing guidelines on trials with so little diversity can lead to delayed disease detection and higher mortality rates, said Dr. Carol Mangione, chair of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, a panel of national experts who make recommendations about services such as screenings, behavioral counseling, and preventive medications. Its recommendations play a major role in determining which tests and procedures health insurance companies will agree to pay for.

“We know that Black people get diagnosed with and tend to die more from colon cancer, for example,” Mangione said. “But we don’t have sufficient evidence to say that there should be a different recommendation for Black people, because Black people have not historically been well represented in the clinical trials.”

When Buff was diagnosed with lung cancer, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended screening for people who were 55 and older and had a smoking history of 30 “pack years,” which means the person smoked an average of one pack of cigarettes a day for three decades. Buff made the cut.

But a 2019 study published in JAMA Oncology found that under those parameters, 68% of Black smokers would have been ineligible for screening at the time of their lung cancer diagnosis, compared with 44 percent of white smokers. In 2021, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force lowered the recommended screening age for lung cancer to 50 and reduced the number of pack years to 20.

The new guidelines make 8 million more Americans eligible to be screened. But that’s not the only problem that needs to be addressed, said Dr. Gerard Silvestri, a lung cancer pulmonologist at the Medical University of South Carolina.

“It doesn’t matter if a bunch more African Americans are eligible if they have no coverage, distrust the medical system, and have no access,” Silvestri said.

“You might exacerbate this disparity,” he said, “because more whites will also become eligible and are likely to have more access.”

Silvestri co-leads the Medical University of South Carolina’s portion of a $3 million, four-year Stand Up to Cancer grant-funded project focused on addressing lung cancer disparities. Researchers in the multicenter collaboration — which also includes the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and the Massey Cancer Center at Virginia Commonwealth University — said better screening rates will improve outcomes in underserved communities.

“Patients of color, particularly Black patients, tend to have less access to care, less timely follow-up when there’s an abnormal finding, and later stages of diagnosis,” said epidemiologist Louise Henderson, principal investigator for the study at the Lineberger center.

It takes concerted community efforts to contend with the suite of health disparities that result in poor outcomes for communities of color, experts said. The lung bus that Buff visited is just one example of how cancer researchers are rolling out programs in rural communities. The Atrium Health Levine Cancer Institute in Charlotte, North Carolina, launched the effort in March 2017 to make screening more accessible to underserved people in vulnerable communities who are either uninsured or underinsured.

The bus operates in 19 counties in North and South Carolina. In an analysis published in the journal The Oncologist in 2020, the Levine Cancer Institute said the project had identified 12 cancers in 550 patients and called the results “policy changing.”

By September 2021, the researchers said, the bus had identified 30 cancers in 1,200 screened patients. “Of which 21 were at the potentially curable stage,” said Dr. Derek Raghavan, president of the Levine Cancer Institute and lead author of the analysis. About 78% of the people screened were poor and from rural areas, he said, and 20% were Black Americans.“

You can overcome disparities of care if you really want to,” Raghavan said.

The Lineberger center also partnered with federally qualified health centers in the Raleigh-Durham area and recruited community health advisers to educate patients about the risks of lung cancer and the ease of being screened. It also trained patient and financial navigators to assist with the often-overwhelming aftermath of a diagnosis.

Recent studies in JAMA Oncology and the Journal of the National Cancer Institute have found that Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act improves overall cancer survival among all racial and ethnic groups and reduces racial disparities in cancer survival. Among the three research sites participating in the lung cancer disparities project, the Massey Cancer Center in Virginia is the only one in a state that expanded Medicaid.

Vanessa Sheppard, associate director of community outreach engagement and health disparities at the center, said she has seen anecdotal evidence that expanding health care coverage improves cancer screening rates.

Nonetheless, awareness about screening remains low in the Black community. Sheppard believes that may be because general health care providers are not educating patients on the available screening tools.

A low-dose CT scan, for example, is one of the most powerful tools available for detecting lung cancer early and reducing deaths. But according to the 2022 Lung Health Barometer from the American Lung Association, nearly 70% of people don’t even know that type of screening is available. And according to Silvestri, only a small percentage of those who are eligible actually get screened.

Perhaps the final hurdle is erasing disparities in who gets follow-up care after screening. A study published in 2020 in the journal BMC Cancer found that Black patients who had been referred to a lung cancer screening program were still less likely than white patients to get screened and that they had longer delays in seeking follow-up care when they did get screened.

Henderson said some patients may mistakenly believe lung cancer is untreatable and simply don’t want to hear bad news.

Sheppard said screening can be used to educate and build trust with patients.“

Once we get people in the system, it’s up to us to make sure they know what’s expected, that it’s not a one-time thing, and that we are embedding them within the system of care,” she said. “I think that’s going to help a lot.” (HN/KHN)